Immigration Nation, a six-episode docuseries that provides a rare view of the internal workings of immigration enforcement—and its impact on individuals and families—began streaming on Netflix in August. The series provides a unique, up-close look at U.S.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) operations in communities from 2017 to 2020 and the real-life impact of our draconian approach to immigration enforcement.While ICE agreed to allow the producers of the series to film its operations, the agency attempted to delay the film’s release after viewing the final product until after the 2020 presidential election. Trump administration officials even threatened to sue to block parts of the film from airing altogether. The film serves as an indictment of our approach to immigration enforcement and the executive branch’s unchecked authority in regulating immigration in the United States.

These are the stories ICE tried to cover up.

The U.S. Continues to Separate Immigrant Families

The series covers the Trump administration’s 2018 family separation policy that was carried out by U.S. Customs and Border Protection—an agency with a long and documented history of impunity.

From detention, a father named Josue recounts when U.S. Customs and Border Protection dragged his screaming 3-year-old son away from him.

Emilio, a Guatemalan in his early teens, displays behavioral issues at school as he struggles to adapt to living with his aunt after being separated from his now-detained father at the border.

Children who are suddenly separated from a parent are at greater risk of developing chronic mental health or serious physical conditions.

While the Trump administration has claimed that it has brought an end to family separation, the docuseries demonstrates that our immigration enforcement policies routinely lead to the separation of families.

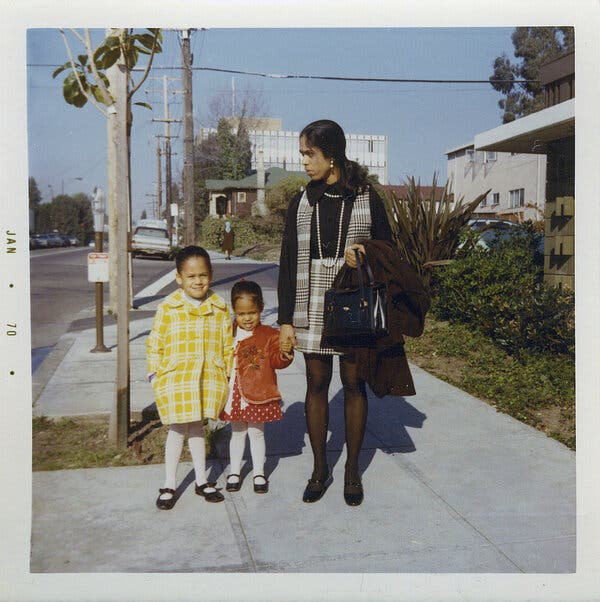

4.1 million U.S. citizen children under the age of 18 live with at least one undocumented parent.The filmmakers document how our enforcement policies routinely lead to the separation of these families. Approximately half-a-million have experienced the deportation of at least one parent.

The U.S. Deports Veterans of Its Own Military

The series also documents how the United States has and continues to deport military veterans, including those who have served in combat. Noncitizens who serve in our military are often unaware that non-violent criminal histories can make them deportable. Last year, the Government Accountability Office revealed that ICE was not following procedures intended to minimize these deportations.

Once deported, veterans may be unable to access benefits they earned while serving, like disability or retirement pay. The series documents the struggle of a man named César, a former Marine, who put his life on the line for our country. only to be deported for a nonviolent drug offense. His only potential avenue of relief is a pardon from the Governor of New Mexico.

Creating Barriers to Family Reunification

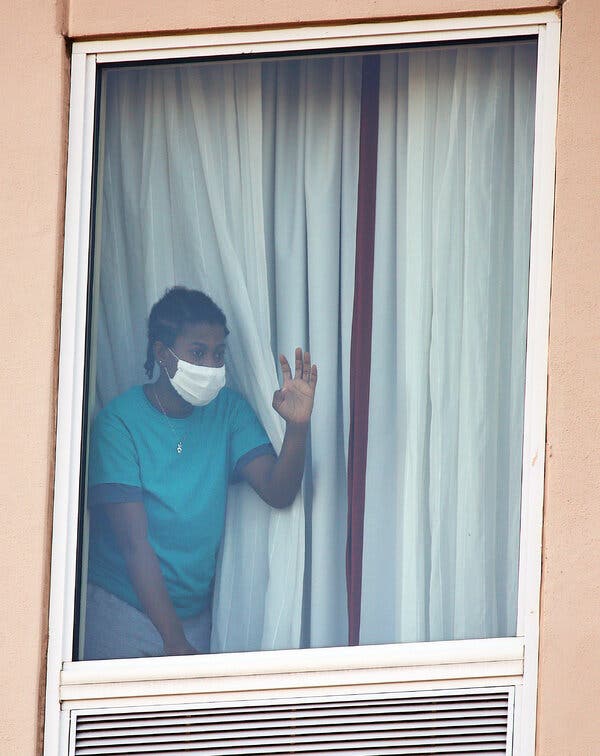

The series also highlights the story of a woman named Deborah from Uganda who was attacked with acid by men sent by her ex-husband. While she was fortunate to be resettled in the United States as a refugee, the film documents her desperate five-year wait to be reunited with her children.

Over the past four years, the Trump administration has slashed the refugee cap from 110,000 spots to 18,000. This year, the government is on track to leave thousands of those reduced spots empty.

Deterrence at All Costs

Perhaps most devastating are the stories of families who the immigration system separates permanently.

The final episode focuses on a policy known as prevention through deterrence, a strategy the United States has pursued since the 1990s. The tactic uses barriers, agents, and technology to prevent immigrants from crossing the border in safer areas. It forces them deep into dangerous terrain like the Sonoran desert. This often leads to death through exposure.

The filmmakers spoke with staff of the Pima County Medical Examiner’s office in Arizona about the over 7,000 bodies found on the U.S.-Mexico border since 1998.

The series also follows Camerina in her years-long search for the remains of her son. Her story highlights the difficulty in identifying, or even finding, remains of a person who dies in the desert. Over 3,000 people who have been reported missing have not been identified.

The Fight Continues

The series also documents the way that communities in the U.S. have challenged immigration enforcement practices, with an emphasis on state and local collaboration with the federal government.

Citizens of Charlotte, North Carolina fought t back against their police department’s collaboration with ICE through a 287(g) agreement. This program allows the Department of Homeland Security to deputize state or local law enforcement officers to perform the functions of federal immigration agents. This allows any interaction with law enforcement, including a traffic violation, to turn into potential deportation and can lead to bias-based policing.

It is important to remember that these heartbreaking stories are a part of daily life for real people across the United States. Those portrayed in Immigration Nation share an intimate, vulnerable view of some of the most painful moments of their lives. We must honor them by continuing to fight the policies that cause that pain. It is time to reimagine our approach to immigration enforcement.

Source: The Stories From Immigration Nation ICE Didn’t Want You to See